Along the spine of the Klamath Mountains, the Bigfoot Trail winds for 360 miles from the oak woodlands of the Mendocino National Forest to the fog-washed forests near Crescent City. It crosses six national forests, a national park, and a state park. It passes through one of the most botanically rich temperate regions on Earth, home to at least 32 species of conifers. It also passes, increasingly, through the ecological fingerprints of wildfire.

Fire is not new here. For thousands of years, Indigenous peoples used low-intensity fire to shape these forests—opening meadows, tending food plants, and guiding wildlife. What is new is the scale, severity, and frequency of modern wildfires driven by climate change and a century of fire suppression. To understand what this shift means for the Bigfoot Trail and the people who steward it, BFTA volunteer and GIS analyst Dallas Morgan set out to quantify something we’ve all been feeling on the ground: how much of the trail has burned since the Alliance was founded in 2015.

A Trail That Crosses Fire’s Footprint

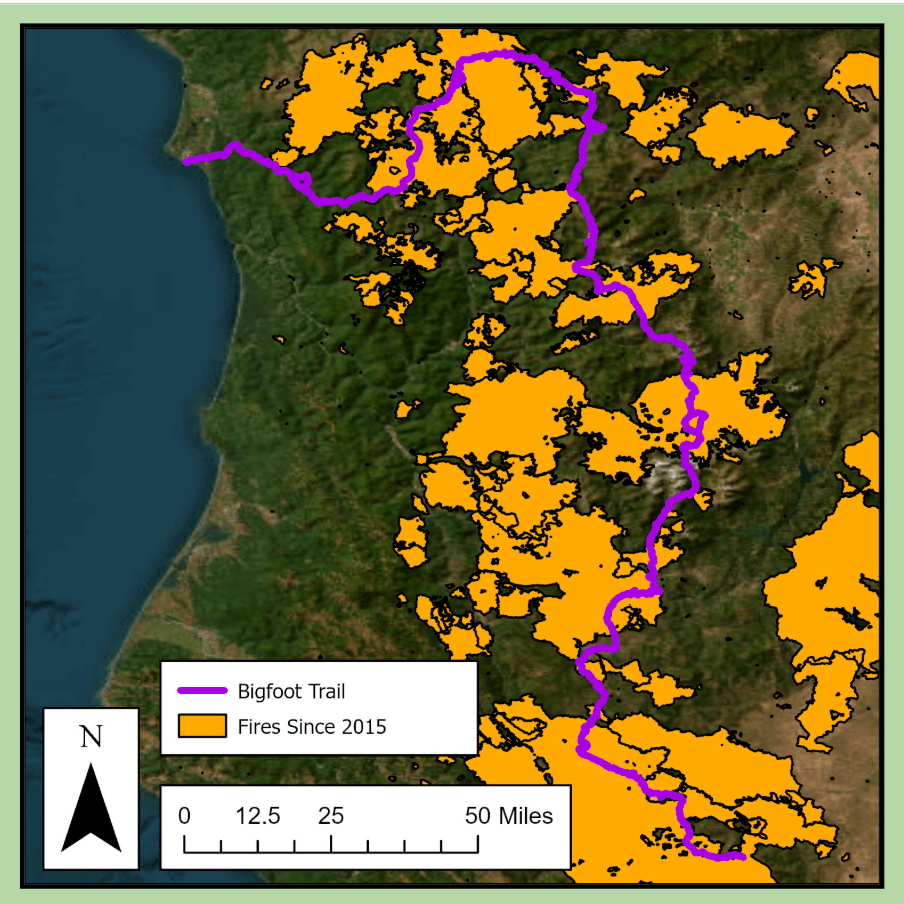

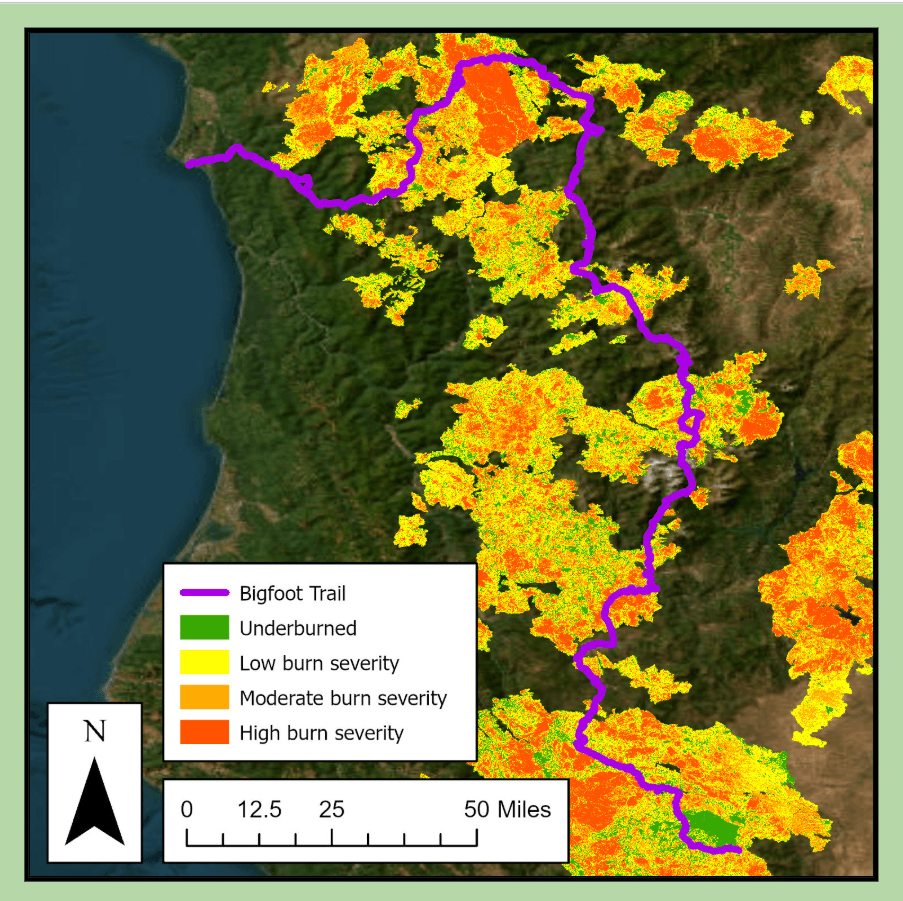

Using fire perimeter data from CAL FIRE and burn-severity maps from the Monitoring Trends in Burn Severity (MTBS) program, Dallas overlaid a decade of wildfire history onto the Bigfoot Trail route BFT Fire Impact Slides. This was not just a single map, but two parallel analyses—one based on fire boundaries, the other on burn intensity—to make sure the results were as accurate as possible.

The outcome was both sobering and clarifying.

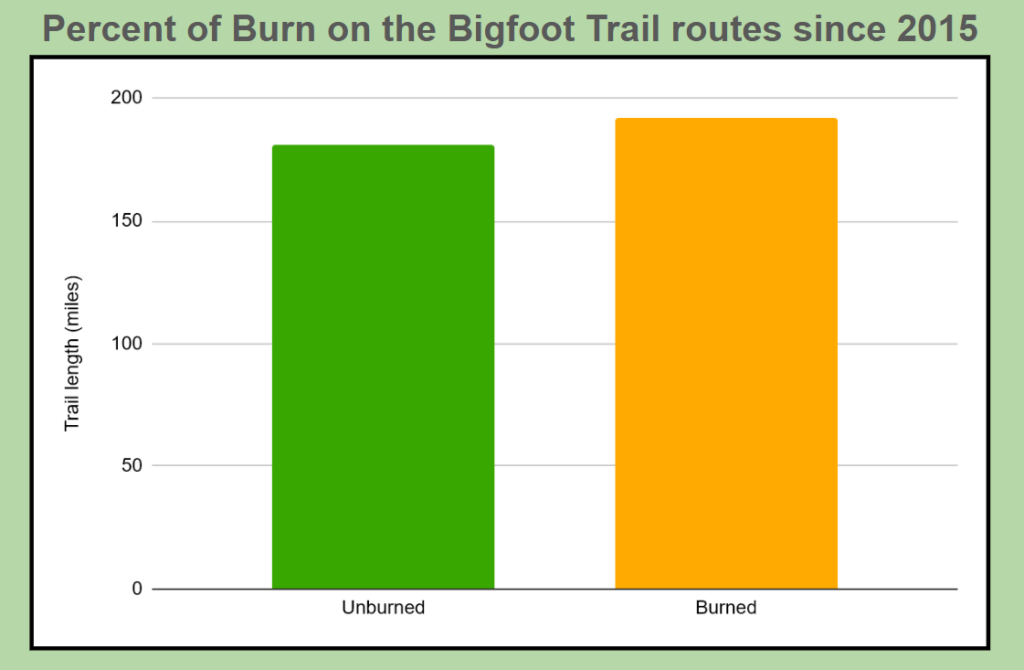

- Since 2015, more than half of the Bigfoot Trail—51%—has burned.

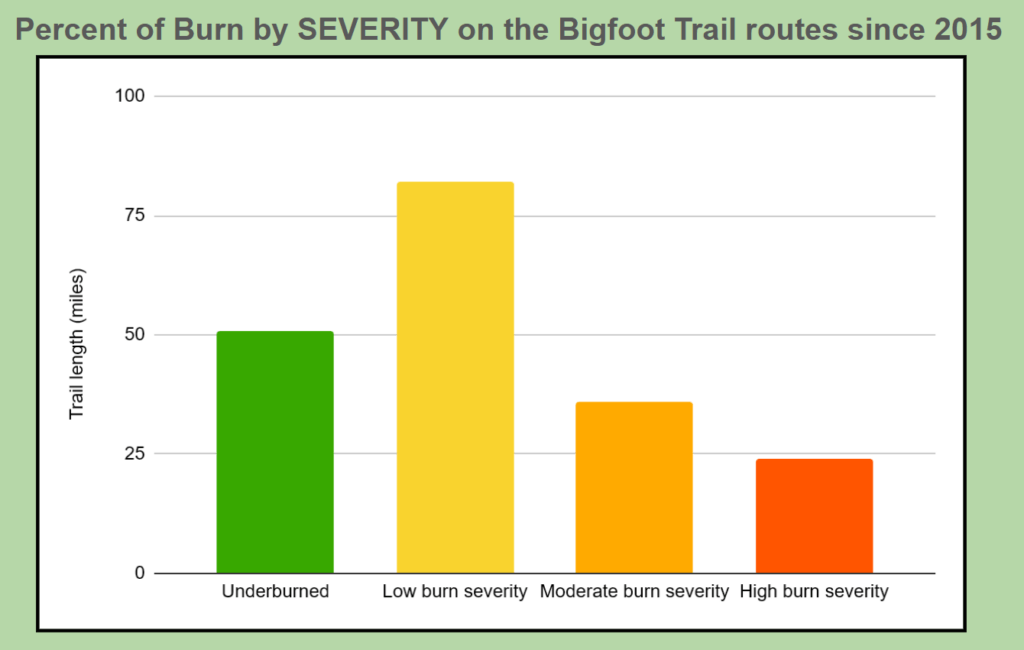

- Within that footprint, about 60 miles of trail burned at moderate severity or higher.

Those numbers don’t mean that 180 miles of trail are now bare ground. In many places, fire moved gently through the forest, clearing brush and renewing understories. In others, it burned hot, killing mature trees, destabilizing slopes, and filling drainages with fallen wood. For trail crews and hikers alike, these differences matter. A low-severity burn might make a trail easier to maintain. A high-severity burn can transform it into a maze of jackstrawed logs and eroding hillsides.

Why Long Trails Matter

One of the most powerful insights in Dallas’s work is not just how much of the trail has burned, but what a long-distance trail allows us to see. The Bigfoot Trail cuts across administrative borders—six national forests, a national park, and a state park—but fire does not respect those lines on a map. Neither do watersheds, wildlife, or plant communities.

By tracing wildfire across the entire 360-mile corridor, the Bigfoot Trail becomes a kind of ecological transect through the Klamath Mountains. It shows us how fire patterns shift from the dry interior ranges to the wetter coastal mountains, how different forest types respond, and how a changing climate is rewriting the disturbance regime of an entire region BFT Fire Impact Slides.

From Data to Dirt: How We Use This

For the Bigfoot Trail Alliance, this analysis is not academic. It directly shapes how we care for the trail.

Knowing where moderate- and high-severity fire has intersected the route helps us prioritize:

- Where trail crews will face the heaviest log loads

- Where tread is most likely to erode or collapse

- Where regrowth may soon obscure the route

- Where hikers will encounter the most challenging conditions

Dallas’s analysis also showed that the two independent methods—fire perimeters and burn-severity rasters—produced almost identical results, differing by less than 0.6% in burned trail length BFT Fire Impact Slides. That level of agreement gives us confidence that what we’re seeing on the ground is real.

In a future where wildfire is no longer an occasional disturbance but a defining force, this kind of data allows us to be proactive rather than reactive. It helps us send crews where they are most needed, plan multi-year restoration efforts, and communicate honestly with hikers about what they will encounter.

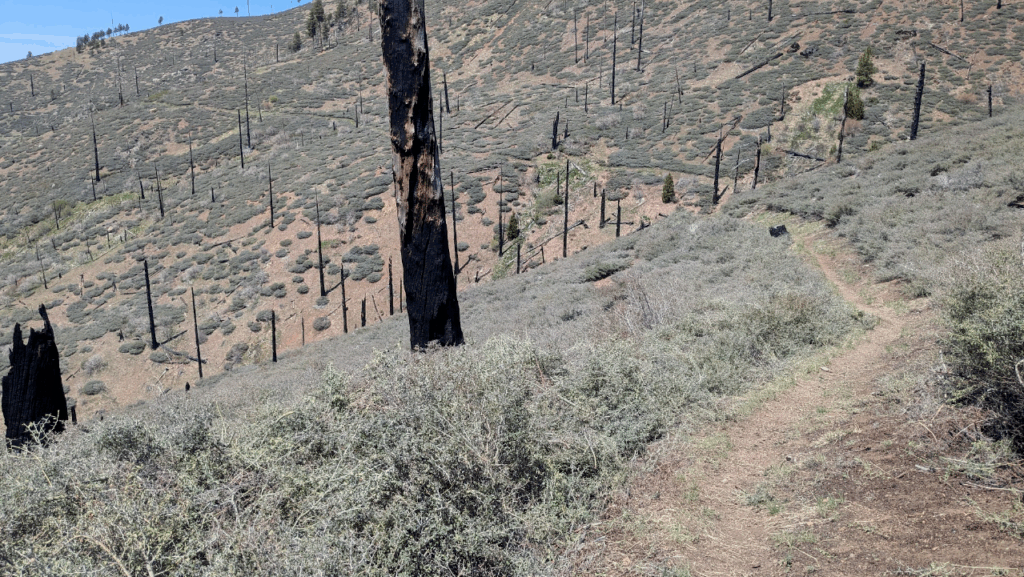

Walking Through Change

If you’ve walked the Bigfoot Trail in recent years, you’ve already felt this story under your boots: the sudden openness of a burned ridge, the tangle of fallen snags across a tread, the wildflowers blooming in ash-rich soil. These are not signs of a dying landscape, but of a landscape in flux—one that is grieving old forests and growing new ones at the same time.

Fire has always been a storyteller in the Klamath Mountains. Now, with the help of careful mapping and long-distance trails, we are learning to read its language across hundreds of miles.

Leave a Reply